Dogs in Antarctica - Huskies

"The departure of the last remaining huskies from Antarctica marks the end of an era . . . It will always be difficult for those who have not shared the experience to understand the pure delight of driving behind dogs and being utterly dependent on them for life itself . . . "

HRH the Prince of Wales - foreword to the book "Of Dogs and Men" by Kevin Walton and Rick Atkinson

Dogs first arrived in Antarctica on the 17th of February 1899 when 75 were landed by the ship Southern Cross of the British Antarctic Expedition of 1898 - 1900 at Cape Adare in the Ross Sea area. The landing was followed by a four day blizzard which trapped seven men ashore, they had a large tent and survived by bringing all of the dogs in to lie on top of them to keep them warm, dogs in Antarctica proved their worth from the outset.

In April, one of the dogs was thought lost when it was blown out to sea on an ice floe, it turned up in good condition and spirits ten weeks later (around midwinter) demonstrating the ability of dogs to survive in Antarctica. Ole Must and Persen Savio, two Norwegian Laplanders of 22 and 21 years respectively were the first two people to drive dog teams in Antarctica.

The last dogs were taken from Antarctica on Feb 22nd 1994, a consequence of an environmental clause in the Antarctic Treaty that required non-native species to be removed. In the case of dogs, specifically because distemper (a disease of dogs) could potentially spread from the dogs to the native seals of Antarctica.

Two dog teams each

pulling a sledge camps for the night, Antarctica 1970's.

In between these times dogs usually huskies brought from Greenland or other places in the Arctic were an integral part of life in Antarctica. They were used sometimes well and sometimes badly, they played a fundamental part in the exploration of the continent and in the science that was carried out in Antarctica when the scientific age took over from the Heroic Age. Men and dogs relied on each other for survival and many of these loyal workers and companions paid the price with their lives.

They were there for the practical purpose of transportation by pulling sledges before reliable mechanized transportation was available. Reliable mechanized transport came quite late to Antarctica, much later than in the rest of the world due to the particular challenges posed by cold temperatures and rugged terrain. Dog teams were used as the reliable transportation of choice by many nations through the 1960's and into the 1970's. After this time they were retained on many bases as a back-up to mechanized transport or for "recreational purposes.

Dogs and sleds are quick, flexible and able to traverse most of the terrain that Antarctica has to offer, there are no roads or even trails in Antarctica due to the ever moving snow and ice. Inevitably in time dogs were replaced by snowmobiles, though this happened rather slowly. As technology and operating techniques progressed and frequent mechanical break downs reduced, so the mechanical pullers of sleds outperformed the canine. There are also the facts that unused snow mobiles just sit awaiting the time when they are used whereas dogs need year-round feeding and care and that the effective operation of a dog team requires a skill to be learned and experience. From the 1960's on dogs were kept in Antarctica at an ever decreasing number of bases, Many generations of Antarctic personnel on scientific bases regarded their experiences in Antarctica as being greatly enhanced by the presence of the dogs and the possibility of recreational sledging trips with them.

Dogs in the Heroic Age 1900-1922

- The first significant sledging journey made

in Antarctica was by Ole Jonassen, Otto Nordenskjold and

Jose Sobral in 1902 during the Swedish Antarctic Expedition

of 1901-1904. The three men made a 380 mile round

trip in 33 days from Snow Hill Island at the Eastern tip

of the Antarctic Peninsula. It was the first fully recorded

dog sledge journey and for many years, the longest undertaken.

Like many of the expeditions of the Heroic Age lessons were

learned the hard way including the dogs finding the bag

of the men's food which they promptly ate along with

part of the sack.

- Many of the expeditions of the Heroic Age at

least experimented with dog teams. Early on Scott

and Shackleton tried ponies too though they were found to

be far less successful as they sank deep into soft snow,

were more likely to break through crevasse bridges and very

difficult to get out again if they did. Ponies need bulky

food which had to be transported to Antarctica with no local

source of supply. Dogs on the other hand could be fed on

seals and penguins and if push came to shove (as it sometimes

did) they could eat each other or provide food for the men

who used them. Early experiments with the then fledgling

technology of internal combustion engine powered tractor

sleds were unsuccessful due to very poor reliability.

- The best demonstration of the effectiveness

of dog teams for transport is from Roald Amundsen's

Norwegian Antarctic Expedition whereby Amundsen led a team

of five men to become the first to reach the South Pole

in 1911. The use of dogs for transport was a vital

part of Amundsen's success with rival Robert Scott's

team of five reaching the pole though all dying on the way

back from the effects of starvation, hypothermia and probably

vitamin deficiency and dehydration. Amundsen's team

all returned in good condition having actually put weight

on during their trip. What is less well known however is

that Amundsen set off with 52 dogs and returned with 11.

The remainder were killed at stages along the way and were

eaten by men and dogs alike. They covered 1,860 miles in

89 days going to and from the pole, 10 days less than they

had scheduled for. Picture taken at the South Pole, men

pose, dog looks nonchalant.

- The eleven dogs that returned with Amundsen

from the pole were given to the expedition of Australian

Douglas Mawson in Hobart when Amundsen stopped off there

on his return from the pole. These were taken down

to Antarctica again on the Aurora, Mawson and most of his

people were already in Antarctica, it was the middle summer

of a two winter and three summer expedition and the Aurora

had sailed back to Australia for provisions and to escape

the Antarctic winter. On return from the pole therefore,

those dogs had sailed to Australia and back to Antarctica

once again for a further winter.

- The dogs that were used in Antarctica were working animals,

while they were given names by the men who cared for and

used them for sledge travel, they should not thought of

as pets, they were frequently described as being closer

to their ancestral wolf than to what we think of as a domesticated

dog as this passage demonstrates.

Fights were very common and cannibalism not unknown if no-one was there to break up a fight.

On May 23 (1913) Lassie, one of the dogs, was badly wounded in a fight and had to be shot. Quarrels amongst the dogs had to be quelled immediately, otherwise they would probably mean the death of some unfortunate animal which happened to be thrown down amongst the pack. Whenever a dog was down, it was the way of these brutes to attack him irrespective of whether they were friends or foes.

Home of the Blizzard - Douglas Mawson - Ernest Shackleton having learned the lessons

from the use of ponies and dogs in Antarctica had intended

to cross the continent from coast to coast via the pole

in his 1914-1917 expedition. While his ship was

beset by ice and later crushed and sunk, the dogs were valuably

used in hauling men, lifeboats, equipment and stores across

the ice of the Weddell Sea as the expedition tried to reach

land and safety. Sadly for the dogs, they could not be taken

in the lifeboats and were shot as the sea ice began to decay

and open water was reached (along with the ships cat).

Dogs in the Scientific Age

The Scientific Age in Antarctica is the period following what was called the Heroic Age of exploration in Antarctica. This is when efforts were made to explore the less obvious geographic features and to discover more about what Antarctica is like, why it is the way it is and how it fits in with the rest of the world.

Dogs proved themselves and lessons were learned about how they should be treated with dog handlers training in the Arctic with experienced people about how to handle them and get the best from them before going to Antarctica. Techniques were perfected, the amount of work that could be done was understood and the amount of food needed by man and dog calculated to optimize health and work rate.

Dogs were used by many nationalities in all parts of Antarctica, they were the transportation method of choice as well as being invaluable for helping with morale at many bases for long after they were replaced by mechanical forms of transport. The British Antarctic Survey and Australian Antarctic Survey used dogs for longer than other nations and to good effect still even when some nations had gone exclusively over to mechanized transport. Dogs were still considered to be the most effective form of transport in mountainous areas into the 1960's when they were supported by aircraft which would land food to re-supply the teams in the field and take geological samples out with them.

The Science of the Sledge Dog

In the 1950's the scientific method began to

be applied to sledge dogs and sledging, especially nutrition.

A scientist from Cambridge was appointed as a dog physiologist

to the British Antarctic Survey base at Hope Bay. He found that

a smaller more sturdily built dog could out-pull a heavier one

and came up with an "optimal" sledge dog:

In the 1950's the scientific method began to

be applied to sledge dogs and sledging, especially nutrition.

A scientist from Cambridge was appointed as a dog physiologist

to the British Antarctic Survey base at Hope Bay. He found that

a smaller more sturdily built dog could out-pull a heavier one

and came up with an "optimal" sledge dog:

- Height at shoulder - 23" (58.5cm)

- Nose to tail - 60" (152.5cm)

- Width at shoulder - 10" (25.5cm)

- Width at hip - 8" (20cm)

- Weight, around: 90lb (41kg)

A sledge load of 120 lb (54.5kg) per dog was considered to be a fair maximum, this was confirmed with strain gauges measuring the pull a dog could exert, though this could vary by 50% from day to day dependent on a number of factors such as temperature, diet, snow surface and even the mental effects of a long monotonous journey on the dog.

A dog team would usually consist of nine dogs often led by a bitch. Lighter dogs went at the front and heavier workers to the rear. The dogs gave the appearance of enjoying human company and attention and enjoyed their jobs pulling sledges. The center trace was most commonly used, though at other times a fan trace would be used to good effect. In good conditions a team on the Antarctic Peninsula might average 16 miles (26 km day).

Investigations into nutritional requirements were also made. Sledge dog food requirements were found to vary quite widely from dog to dog, an average requirement was around 2,500 kcal per day when idle and at least 5,000 kcal per day when actively hauling heavy sledges over long distances. These amounts are about 75% of that required by a human under similar conditions. The requirement for active sledging is about the same for a human and dog at 5,000 kcal per day each. The men of course don't continually pull the sledge under those conditions, they do however frequently ski alongside or in front of the sledge and will get off and push through especially difficult terrain such as broken up ice and soft snow. Sledging with dogs is not the restful pursuit that may be imagined!

Where possible dogs were fed with seal meat which was found to be the best overall food, given with blubber and skin in the winter and when working and with less blubber in the summer months when less energy is needed to maintain body temperature and condition. Both dogs and men would often lose weight and condition when out in the field travelling and camping daily. Each dog would be fed 7lb (3.18kg) of seal meat and blubber on alternate days in the winter months, that averages out to the equivalent of about 2 x 8oz. steaks (protein) + 5 x 8oz. blocks of butter (fat) per day.

When travelling dogs would be given pemmican (dried

ground meat with fat and other additives) at a rate of 1.25

lb (0.57 kg) per day which when supplemented with seal meat

kept them in good condition. Pemmican was not such a good diet

for the dogs, often leading to diarrhoea, up to 30% of the food

was passed directly out in the faeces without being absorbed

(measuring that was a project I'm glad I wasn't involved

in!). Dog pemmican based on what humans would eat was replaced

by a more dog-friendly version called "Nutrican" (a

trade name) which itself underwent improvement with experience.

Seal meat, fresh or frozen remained the optimal diet, though

there is a difficulty in making sure that meals are uniform

in terms of the size of the helping and relative amounts of

meat, offal, blubber and skin.

When travelling dogs would be given pemmican (dried

ground meat with fat and other additives) at a rate of 1.25

lb (0.57 kg) per day which when supplemented with seal meat

kept them in good condition. Pemmican was not such a good diet

for the dogs, often leading to diarrhoea, up to 30% of the food

was passed directly out in the faeces without being absorbed

(measuring that was a project I'm glad I wasn't involved

in!). Dog pemmican based on what humans would eat was replaced

by a more dog-friendly version called "Nutrican" (a

trade name) which itself underwent improvement with experience.

Seal meat, fresh or frozen remained the optimal diet, though

there is a difficulty in making sure that meals are uniform

in terms of the size of the helping and relative amounts of

meat, offal, blubber and skin.

| Composition | Seal meat with blubber |

Lean seal meat |

Pemmican | Nutrican | Improved Nutican |

Halibut* | Stockfish* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein % | 18 | 27 | 63 | 29 | 21 | 23 | 32 |

| Fat % | 39 | <1 | 28 | 42 | 40 | 4 | 1 |

| Carbohydrate % | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 23 | 0 | 0 |

| Energy kcal / lb | 1973 | 510 | 2352 | 2520 | 2456 | 590 | 640 |

| Water % | 45 | 72 | 6 | 9 | 5 | 70 | 65 |

*Halibut and stockfish are often used as a diet for dogs in the Arctic - total % adds up to less than 100, the difference is ash and minerals.

Experiments from 1932 on treadmills showed that enough food could increase a dogs work rate by a factor of three. In one experiment a dog ran for 17 hours with a 5 minute rest each hour, covering 82 miles (132 km) and climbing the equivalent of 14 miles (22.4 km). With low external temperatures to prevent overheating and sufficient water and food, dogs could run virtually tirelessly when exercising aerobically. Poorly fed dogs in the field that were losing weight would often be reported to become more difficult to drive, to lay down exhausted at halts and more difficult to rouse at the start of the day.

Occupational osteoarthritis was found to be a major problem amongst sledge dogs which limited their useful working life to about 7-8 years. The result of continuous work led to erosion of cushioning cartilage pads in the hips and shoulder joints of the dogs from continuous exercise under the pressure placed by the sledge harness.

Antarctic and Arctic Sledge Dogs

-

Antarctic

Sledge dogs were slightly larger and stockier than those

of the Arctic, they were required to pull heavier

loads over more uneven terrain rather than at speed over

flatter ice and snow as in the Arctic. Antarctic dogs were

anecdotally more friendly and more docile due to a breeding

out of the wolf traits which are more prized in the North.

Antarctic

Sledge dogs were slightly larger and stockier than those

of the Arctic, they were required to pull heavier

loads over more uneven terrain rather than at speed over

flatter ice and snow as in the Arctic. Antarctic dogs were

anecdotally more friendly and more docile due to a breeding

out of the wolf traits which are more prized in the North.

- Weights differ substantially between individual

dogs with some up to 125 lbs being reported, In

the Arctic, typically sledge dogs are 75-85lbs, in the Antarctic,

they averaged around 95lbs (bitches were 10-20

lbs smaller), weights under 80lb or over 100lb were considered

indicative of over or under feeding.

- Antarctica is colder and windier than the Arctic,

being larger gives a lower surface area to volume ratio

and helped the dogs stay warm in extreme cold temperatures.

Antarctic sledge dogs had long tails with thick fur that

they could curl around themselves in particular to protect

their face and muzzle. When the wind blew, snow would pile

up around a sleeping or resting dog which helped protect

it from the wind and snow, they could be very reluctant

to stir themselves and destroy this hard won protective

layer.

- Some smaller Arctic bred dogs, Samoyeds

used to smoother snow surfaces and warmer temperatures were

taken to Antarctica by Robert Scott in 1911, they were not

used well and their feed (dried fish brought with the ship

to Antarctica) had started to rot so they were not used

on the South Pole trip, though were used successfully from

the base with lighter loads. Their tails were not long enough

to protect them sufficiently when at rest and their paws

bled on the cold hard surfaces that they were not used to

or bred for.

The story of an Antarctic Sledge Dog - Boo Boo

-

1961 - Born at Halley Bay base in Antarctica, 75°35'

South.

1962 - Ran 409 miles.

1963 - Ran 765 miles.

1964 - Ran 1,900 miles.

1965 - Ran 2,000 miles.

1966 - Ran 1,260 miles.

1967 - Ran 1,800 miles.

1968 - Ran 1,290 miles.

1970 - Ran 560 miles.

By 1971, Boo Boo's total mileage was 10,474 on foot (paw). He pulled sledges of over 1,000 lbs accounting for 4,675 tons of supplies moved of which his own contribution was 500 tons. By 1971 Boo Boo was retired, rarely chained up and allowed to wander around the base at will. Much of the summer of 1971 was spent taking pieces from the seal pile to his various "girlfriends", some of whom ended up with significant piles of meat.

The men of the base unofficially named a mountain after Boo Boo whose location remains secret, it is remembered as "Boo Boo's Lost Mountain".

*In the picture Boo Boo is played by a stunt double.

Huskies were finally removed from Antarctica a a consequence of The "Madrid Protocol" - The Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, signed in 1991

"Dogs shall

not be introduced onto land or ice shelves

and dogs currently

in those areas shall be removed by April 1 1994".

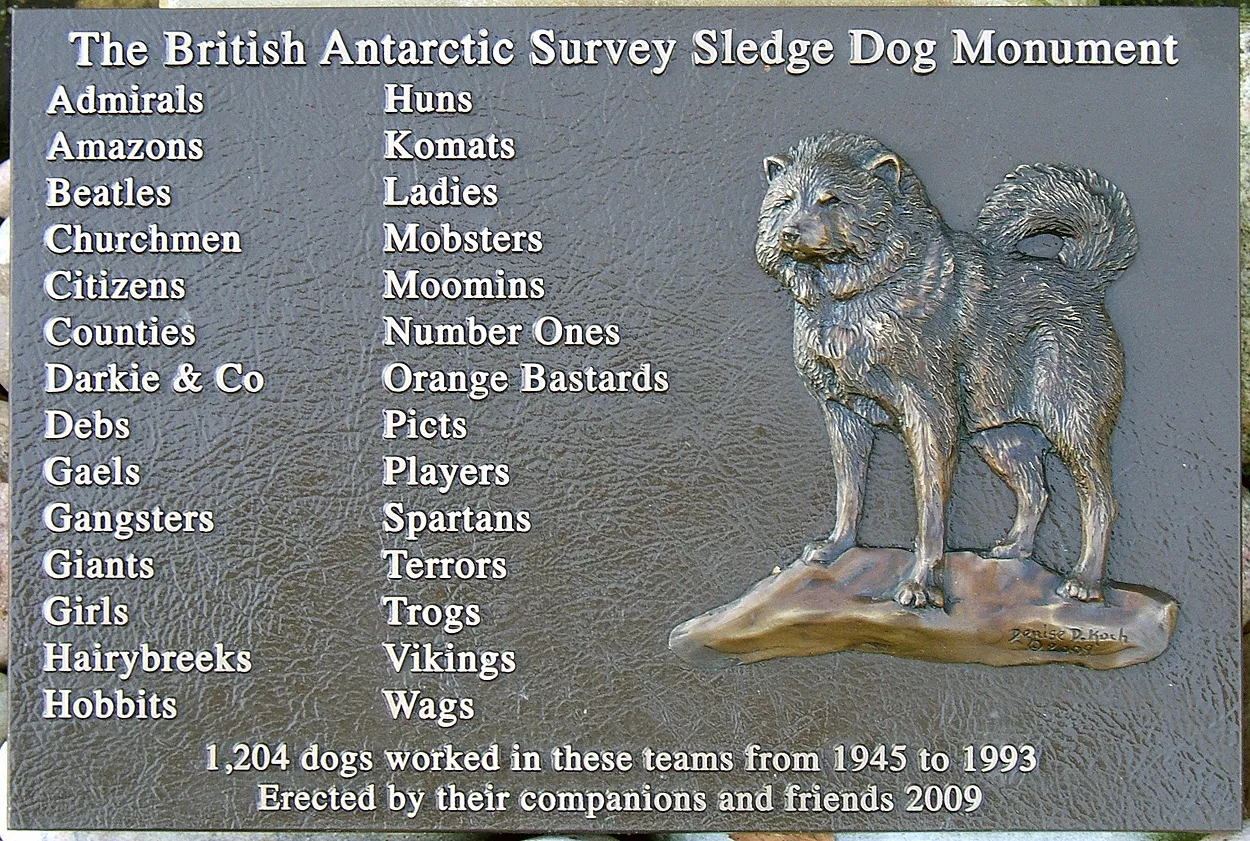

Antarctic Sledge Dog Memorial, SPRI, Cambridge, England

A bronze sculpture of a husky sledge dog of the type used by the British Antarctic Survey in Antarctica (BAS) between 1945 and 1993 made by sculptor David Cemmick was unveiled on the 4th of July 2009. Hwfa Jones, Graham Wright and Dick Harbour, all men who had lived and worked with dogs in Antarctica began the project and raised the funds to pay for the statue.

Originally placed at the British Antarctic Survey headquarters in Cambridge, in October 2015, the sculpture was moved to a new position outside the Scott Polar Research Institute on Lensfield Road in Cambridge. Due to new building work there was no longer a space for it. Thanks to the efforts of Dick Harbour, Hwfa Jones and Graham Wright the custodians of the statue along with Julian Dowdeswell, Director of SPRI a new, and to my mind much better situation, was found where far more people can see the statue in near-central Cambridge right outside the Polar Museum (now much improved, if you haven't been for a few years, it's well worth a re-visit). So alls well that ends well. It was a cold and wet day when I took these pictures which aren't as good as they could be, I like the way the dog looks like he's waiting for someone to come out of the museum. More about the memorial

We would like to thank all the people from around

the world who have donated to the Fund to ensure this monument

has been created. Still so fresh in the minds of those who

sledged with dogs, the monument represents a thousand personal

stories; most of which will never be told in any official

documents. These dogs made possible almost all the overland

journeys in the 20th century and shared in the discovery

of the continent from which they are now forever banned.

Hwfa Jones

Picture credits, copyright pictures used by courtesy

of: NOAA, Corel corporation, Drummond Small

References:

Jones, H. 2006 -

The Doggy

Men

Walton, K. and Atkinson, R, 1996 -

Of Dogs and

Men

Orr 1965 - Food Requirements of Dogs on Antarctic Expeditions,

Bellars 1969 - Veterinary studies on the British Antarctic

Survey's sledge dogs,

Bellars and Godsal 1969 - Veterinary studies on the

British Antarctic Survey's sledge dogs II, occupational

osteoarthritis